Isobel Lawrence, CPOM Research Associate, UCL

Back in 2011 I completed a Masters project at CPOM working on airborne radar retrievals of snow on sea ice, and then went on to work at UCL processing CryoSat-2 data. I left for a few years to pursue Science Communication, but the CPOM bug eventually caught up with me and I returned in April this year to start my PhD working on CryoSat-2 retrievals over sea ice.

Last week I was lucky enough to have the opportunity to attend the first ESA Advanced Cryosphere training course. Held at the University of Leeds, it brought together 60 early career scientists from across the ESA member states, the USA and Asia to learn about how we study the Earth’s frozen regions from space.

On arrival, we all gave a brief overview of who we were, where we’d come from and what aspect of the cryosphere we studied. There was a diverse mix of backgrounds, expertise and interests; from the mountain glaciers of Patagonia, to Himalayan ice caps and the vast Antarctic ice sheet. Not to forget sea ice, which was mine and many others’ “favourite type of ice”.

The 5 days of the school were broken into different topics; Optical remote sensing and mountain glaciers, Synthetic Aperture Radar (SAR) and ice dynamics, altimetry and sea ice, gravimetry and ice sheet mass balance, and radiometry and surface mass balance. The structure was ideal and made the most of the week that we had; the practicals being a fantastic way to implement what had been learned during the morning sessions, and there was plenty of room for getting to know one another and our research interests.

So much was covered during the school, but I’ll just run through my highlights, with an apology and a thanks to anyone who I don’t mention specifically – it was all great!

Following some official welcomes from ESA and the UKSA, it all got going on Monday morning with a lecture by CPOM’s own Andy Shepherd. As he said was his intention, he gave an inspiring overview of the history of Earth observation and the development of high latitude remote sensing. A host of imagery, beginning with the first picture of Earth from space from a V2 rocket in 1946, gave us an appreciation of the incredible perspective remote sensing has given us, and continues to give us, on our planet.

Pete Nienow’s talk, “EO validation and the measurements you can’t make from space”, made the important but often overlooked point that it is vital to carry out fieldwork to calibrate and validate observations from space. And often remote sensing just doesn’t cut it: there was particular focus here on ice sheet processes since these often occur at spatial and temporal time scales too fine to be revealed by satellites, but I took the message to be applied to all fields. You have to get out on the ground to really get a sense of what is going on!

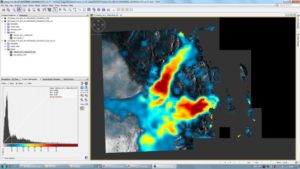

Monday and Tuesday’s practicals were a great opportunity to get hands on with some Sentinel data, something I’ve never looked at before. Frank Paul of the University of Zurich led a practical session where we took advantage of the difference in reflectance of snow at different wavelengths to identify Austrian alp glaciers from Sentinel-2 imagery.

Retrieving glacier area (in turquoise) from Sentinel-2 data. Overlaying with Google Earth allowed us to see how good a fit we had achieved.

And in Tuesday’s practical we mapped the velocity of Greenland’s Nioghalvfjerdsfjorden (I leave it to you to pronounce) glacier by overlaying pairs of Sentinel-1 SAR images taken 12 days apart.

I really enjoyed Twila Moon of the University of Bristol’s keynote talk on ice dynamics. Something she said really spoke to me as an early career researcher: “People always say there are not many more Nature, or other high profile journal publications to come out of ice sheets – there is a ‘we already know everything’ attitude. But if you collect new data and look at it without expectations of what you’re going to see, there is a good chance something amazing can come out of it.”

After decades of satellite observations, I often find myself thinking that I might have missed the boat on ground-breaking EO discoveries, but what Twila said gave me a new enthusiasm to look at the vast amounts of data – and there are VAST amounts of it – with fresh, objective eyes, and maybe be surprised by what I might find.

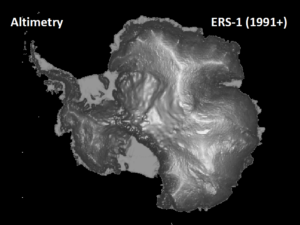

Altimetry day was fantastic. Sinead Farrell gave an excellent overview of all things sea ice and sea ice altimetry, and despite it being my field I still learnt a lot of new stuff. I also particularly enjoyed Noel Gourmelen’s lecture on SARin (CryoSat’s high resolution mode), with the realisation of the potential applications to the work I do, and the animations he showed on the improvement of resolution over ice sheet edges using SARin were impressive.

In the practical for this day, organised by Rachel Tililing and Eero Rinne, we learned how to take elevation data from CryoSat-2 and turn it into sea ice freeboard by distinguishing leads from floes and then interpolating the leads to reconstruct the sea surface. Despite using CPOM’s CryoSat freeboard product nearly every day in the work I do, I’d never actually gone back a stage and done the freeboard retrieval myself, so this was a really beneficial lesson for me.

As well as all the classes, there was also a packed social schedule that gave everyone an opportunity to see the city, or at least the restaurants and bars! As well as Monday’s ice breaker poster session there was an evening of Shuffle Board (if you haven’t played it you REALLY should), and a final lecturer and student dinner on Thursday where we had a final opportunity to wag chins before everyone headed their separate ways on Friday afternoon.

I would like to thank the organisers of the course, especially the tireless Anna Hogg, who put together a fantastic week. Thanks also to all the lecturers and practical organisers who clearly put a great deal of effort into the course material, and were friendly, approachable and happy to have a chat at any time. I learnt a great deal more than I expected, having been used to attending conference talks where the pitch is often too high for many of those who are new to the field. When we all stood up at the end to say what our highlights were it was clear that everyone had taken a lot from the course, and several even expressed they may have been inspired to change the focus of their research paths. Me, I’ll be sticking with sea ice, but have come away with a whole host of new ideas for ways to look at it and a new enthusiasm to do so.