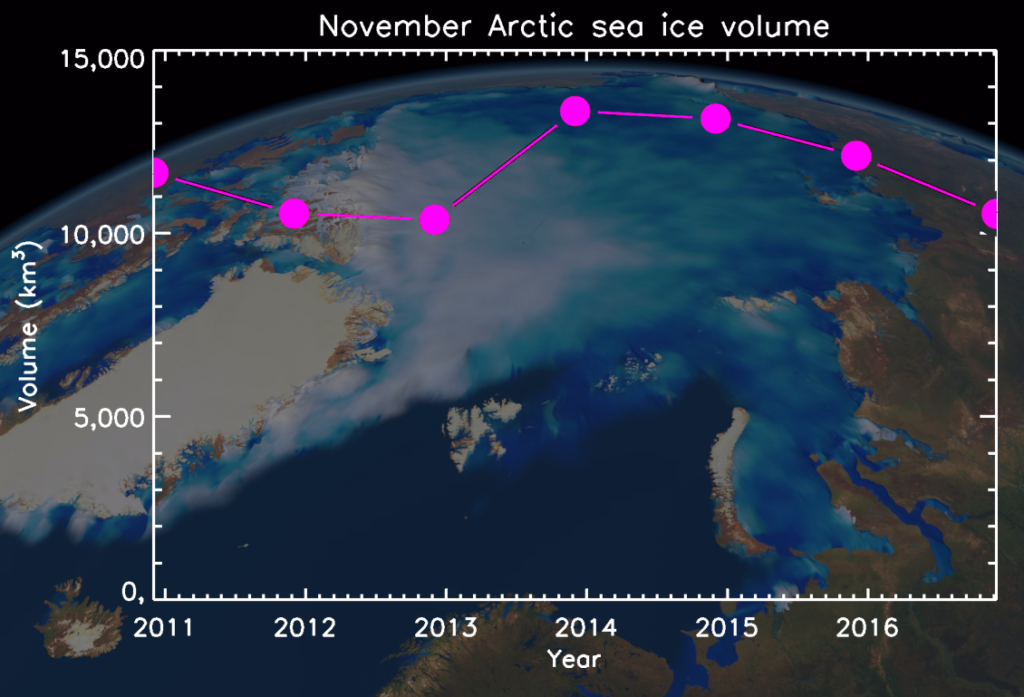

There is set to be only 10,500 cubic kilometres of sea ice in the Arctic this month – the joint lowest of any November on record – according to satellite observations processed by CPOM. Although sea ice volume did not hit a record low at the end of summer, early winter growth has been 9 % slower than usual, leading to today’s conditions.

Trends in early-winter Arctic sea ice volume recorded by CryoSat. Sea ice growth this month has been 9 % lower than usual, and November 2016 is tied as a record low.

The measurements were made using the European Space Agency’s CryoSat satellite, which is dedicated to monitoring the polar regions and is uniquely able to detect the thickness of sea ice floes. Not only are these observations vital for tracking climate change, they are also an essential resource for maritime operators who increasingly navigate ice infested waters.

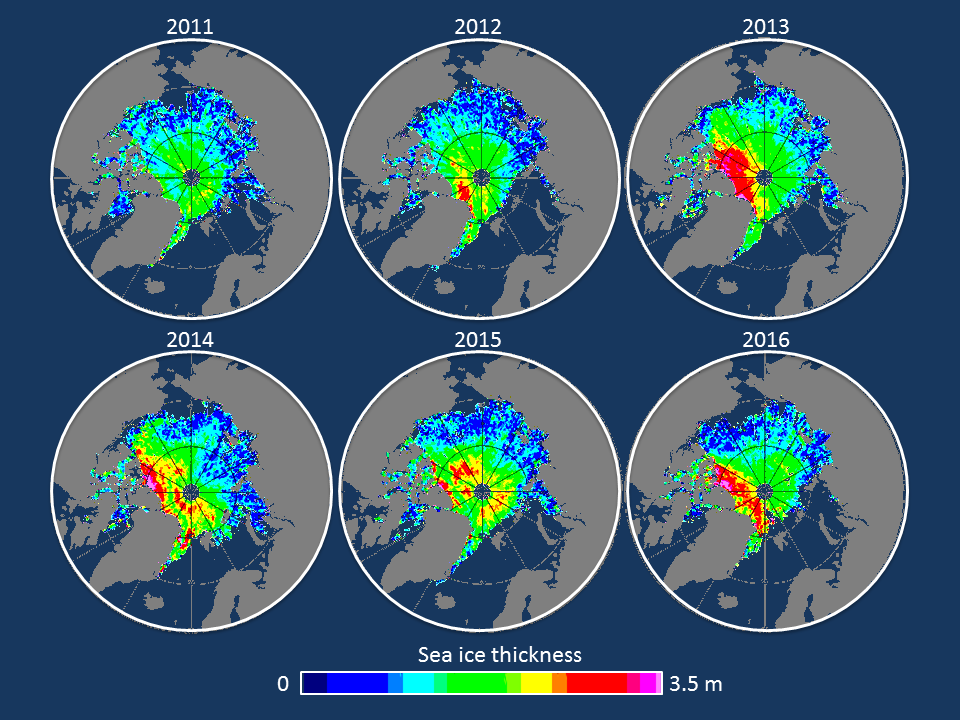

This year, the US National Snow and Ice Data Centre reported that the extent of Arctic sea ice fell to 4.1 million km2 on 7th September – tied with 2007 as the second lowest on record. However, CryoSat shows that the ice was thicker at the end of summer than in most other years – 116 cm, on average – and so there was substantially more ice than in two other years (2011 and 2012). Thicker ice can occur if melting is lower, or if snowfall or floe-compaction is higher.

CPOM Research Fellow Rachel Tilling explained, “Sea ice is highly mobile and susceptible to deformation, so we need to measure its thickness as well as its extent to be sure how much is there.”

However, although the Arctic sea ice pack usually gains 161 cubic kilometres per day in November, this year’s growth has been 10 % lower at 139 cubic kilometres per day, and it is estimated that the final amount will rise to only 10,500 cubic kilometres by the month end.

This would essentially tie with conditions in the Novembers of 2011 and 2012, when levels of Arctic sea ice were at their lowest on record for this time of year.

Although sea ice in the central Arctic is currently thicker than it was in 2011 and 2012, there is far less ice in more southerly regions such as the Beaufort, East Siberian and Kara Seas.

Maps of November Arctic sea ice thickness recorded by CryoSat-2. Although ice is thicker than usual north of Canada, there is less ice overall in southerly regions such as the Beaufort, East Siberian and Kara Seas.

Rachel Tilling added: “Because CryoSat can measure Arctic sea ice thickness in autumn, it gives us a much clearer picture of how it has fared during summer. Although sea ice usually grows rapidly after the minimum extent each September, this years’ growth has been far slower than we’d expect – probably because this winter has been warmer than usual in the Arctic.”

As demand for information on Arctic conditions increases, CryoSat has become an essential source of information for polar stakeholders ranging from ice forecasting services to scientists studying the impacts of climate change.

CPOM Director and Principal Scientific Advisor to the CryoSat mission, Professor Andrew Shepherd, summarised: “In its’ short, six years of life, we have learnt more about Arctic sea ice from CryoSat than from any other satellite mission. But to really understand the role that sea ice plays in the climate system, and the restrictions it places on maritime operations, we must ensure that its measurements are continued into the future.”

A complete assessment of 2016 sea ice conditions will be available from CPOM in the coming weeks.